THE EGYPTIAN SOCIETY OF SOUTH AFRICA

Mummies in SA

MUMMIES IN SOUTH AFRICA

The Egyptian Society of South Africa

gratefully acknowledges the co-operation of

- Dr. Lita Webley, Albany Museum, Grahamstown

- Dr. Billy de Klerk, Albany Museum, Grahamstown

- Dr. Brett Hendey, Durban Natural Science Museum

- Belinda Eisenhauer, Durban Natural Science Museum

- Ansie Steyn, National Cultural History Museum, Pretoria

- Robert Rademeyer, Pretoria

There are 3 recorded ancient Egyptian mummies in South Africa preserved in the following museums –

INTRODUCTION

The study of Egyptian coffins has been somewhat neglected until recently, when scholars in a number of countries began studying the typology, iconography and dating of coffins. Also research groups have started to use radiological techniques to examine Egyptian mummies, adding new analytical dimensions to the examination of mummified remains.

The obvious advantage of these techniques is their non-invasive nature whereby invaluable information of a scientific, Egyptological and paleopathological nature may be obtained without mutilation and destruction of the painted cartonnage case or linen wrappings. New data can be revealed on physical trauma, diseases and nutrition. These techniques have also been utilized in producing three dimensional images and facial reconstructions.

In England, the Manchester Egyptian Mummy Research project was established in 1973, involving a multi-disciplinary team of Egyptologists and scientists to study Egyptian mummified remains. A computerized database, available to researchers, has been established to record information and results of scientific investigations relating to Egyptian mummies in museums world.

ALBANY MUSEUM, GRAHAMSTOWN

The wooden anthropoid coffin containing a mummy, which is displayed at the Albany Museum, was acquired at an uncertain date between 1904 and 1910. To judge by the style of its decoration, the coffin dates from the XVIIIth Dynasty and comes from the region of Thebes in Upper Egypt.

The coffin is 194 centimetres long and 53 centimetres wide at the shoulders. It consists of a lower section, in which the mummy lies (which will be referred to as the box) and a lid. The lid is constructed of three large pieces of wood, two forming the edges, with a narrower piece joining them down the centre. Two other smaller pieces have been attached by means of dowels at the lower right side of the lid, and two small squares of wood have been used to fill in areas of poor quality timber on the lid. The box is constructed of four large pieces of timber which form the sides, with several small pieces attached along the upper edge where the lid would rest, near the head and foot ends. The coffin was painted with a thin layer of white paint which allows the grain of the wood to be seen. In some areas the surface was smoothed by means of a layer of plaster before the paint was applied.

The Lid

The carved representation of the deceased’s face at the upper end of the lid is framed by a striped headdress. Black stripes were painted over a reddish ground. This ground colour is preserved now only at the top of the headdress; elsewhere the natural colour of the wood is visible. The black stripes on the lappets of the headdress do not reach the ends.

The yellow colour of the carved face and the absence of any trace of ceremonial false beard, or the straps to support such a beard, indicate that this is the coffin of a woman. The chest is decorated with a “broad collar” (Egyptian wsh), of ten rows of beads (thirteen between the lappets of the headdress). On each shoulder the collar terminates in a falcon’s head. Below the collar, in the centre of the chest, is the painted image of the protective vulture Goddess Nekhebet, holding two sn-signs in her talons.

The rest of the surface of the lid is decorated with bands of text.

The date and Original Ownership of the Coffin

The stylistic features of the coffin – the white colour, the striped headdress and the bands of text arranged at right angles to one another – indicate that the coffin dates from the XVIIIth Dynasty. The white ground colour limits it to a period not later than the reign of king Thutmosis III. After this king’s reign anthropoid coffins with a black ground were the fashion. The coffin was therefore made and decorated before 1425 BC, the year of Thutmosis’ death. It clearly cannot be dated earlier than 1425 BC, as it cannot be dated, on stylistic grounds, to the beginning of the XVIIIth Dynasty.

The name of the original owner is now uncertain. This is not because the name was never written on the coffin (although it may have been added after the rest of the decoration, if the coffin was bought ready-made from a coffin-maker’s stock), but rather that places where the name would have appeared – the lower end of the central text bands on the box and the lower end of the central text band on the lid – have suffered damage. The damage may have been caused by an accidental flooding of the tomb in a sudden rainstorm. The only remaining traces of the name appear in a text band (XIV), where after the epithet “the Osiris” (i.e. the deceased), traces of three signs remain. The first is a clear N. The other may be y. The owner’s name would therefore have been Ny…, or N[?]y…

A document in the Museum’s files, Note on the Mummy for Pamphlet or Display Stand, states that in an unrecorded year the Albany Museum subscribed a sum of ten pounds to a British Archaeological expedition to Egypt. In return, at some unrecorded time between 1904 and 1910, the Museum received the coffin and mummy, a mummified cat and a few other ancient Egyptian artefacts – ushabti figures and the like.

Written by Robert Rademeyer

ALBANY MUSEUM

Somerset Street, Grahamstown, 6139, South Africa

Tel: (046) 622-2312 Fax: (046) 622-2398

Website: www.ru.ac.za/albany-museum/

Webmaster amwd@giraffe.ru.ac.za

The Natural Sciences and History Museums

Open – Monday to Friday: 09h.00 – 13h00, 14h00 – 17h00

Saturdays & Sundays 14h00 – 17h00

Entrance Fees: R5 adults, R4 children.

One ticket allows entry to both museums.

Observatory Museum

Open – Monday to Friday: 09h00 – 13h00, 14h00 – 17h00

Saturdays: 09h00 – 13h00

Entrance Fees: R8 adult, R5 children.

All museums closed Workers Day, Easter Friday, Christmas Day & New Year.

All other public holidays as for Sundays.

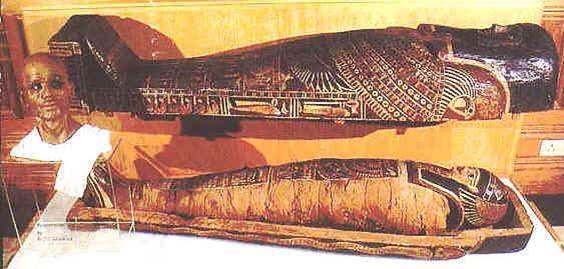

DURBAN NATURAL SCIENCE MUSEUM

In this popular and well-attended museum is a wooden anthropoid coffin with a lid, containing a mummy with cartonnage elements, reputedly from Akhmim, Upper Egypt, of early Ptolemaic date (c. 300 BCE). The coffin and cartonnage elements indicate that they were mass-produced items of the type held in coffin-maker’s workshops. The mummy is that of a minor priest named Peten-Amun (Ptn-’Imn), thought to have died aged about 60 years. The mummy was acquired by the Durban Museum between 1889 and 1910.

It is thought a British army officer, Major William Joseph Myers, brought the mummy from Egypt when he came to South Africa at the end of the 19th century, having served in Egypt for 5 years. Myers was killed on October 30, 1899, aged 41, by an enemy sniper during the siege of Ladysmith in the Anglo-Boer War . Myers amassed the finest 19th century private collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities which he bequeathed to his old school, Britain’s famous Eton College. The collection, comprising 2,000 objects dating from 5,500 BCE to around 350 CE, is going on public exhibition for the first time in Britain and was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York from September 2000 to January 2001.

In November, 1984, the mummy was X-rayed, revealing that the top half of the mummy was almost complete though there were a few molar and pre-molar teeth missing. A minor fracture of one rib was evident though this had healed during the man’s lifetime. The density of the bone in the lower vertebral column suggested some arthritis. A mystery surrounds several missing bones: femur and tibia (left leg), patellae (left and right legs), and feet (left and right). All these bones were replaced by false structures, possibly made of wood and linen stuffing, within the wrappings. The X-rays show that the shoulders have been compressed by the linen wrapping. Rapid decomposition prior to embalming can explain the disordered state of some Ptolemaic mummies, which seem to have disintegrated partly before mummification. As a result, parts of bodies were lost. (Spencer, A.J. (1982) Death in ancient Egypt, Penguin, p 125)

A reconstruction of the head of Peten-Amun, was completed in 1990 by Dr. Bill Aulsebrook who holds a Ph.D. in Forensic Facial Reconstruction. A Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT) scan was taken at the King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban and plastic templates were made from the individual sectional images. The templates were then assembled to form a three-dimensional construction of the skull. Using this reconstructed skull, Dr. Aulsebrook was able to build up the facial musculature features. The bust is displayed alongside the coffin and mummy.

The mummified body is approximately 150 centimetres in length and the coffin itself about 175 centimetres long and 4 centimetres thick.

DURBAN NATURAL SCIENCE MUSEUM

PO Box 4085 Durban 4000, South Africa 1st Floor, City Hall, Smith Street, Durban Telephone: (031) 311 2220 Fax: (031) 311 2242 E-mail: bretth@crsu.durban.gov.za

Website:

www.durban.org.za/artculture/museums/natural.html

Open Monday to Saturday 08h30 – 16h00

Sunday 11h00 – 14h30

Closed Christmas Day & Good Friday

Entrance free

NATIONAL CULTURAL HISTORY MUSEUM PRETORIA

The mummy is currently housed in the African Window exhibition area of this museum and was brought to South Africa during the 19th century from the Fayum. In April 1899, it was recorded that the ‘Staatsmuseum’ received a mummy from government mining engineer J. Klimke. (Register II, p. 279)

The mummy is the victim of bacteriological destructive activity and it was reported that “Its bones are jumbled. The skull and rib cage are shattered but you can still see the profile of the face”. (Pretoria News, July 7, 2002)

In May 1965 the mummy was examined by X-Ray when it was first discovered that some bones were broken and some disorientation of the remains within the wrappings was evident. The jaw and pelvic structures indicate the mummy to be that of a 35 year-old person. Although the sex remains unconfirmed, a non-invasive scan examination in July 2002 at the Muelmed Hospital in Pretoria has led some to believe the mummy is that of a male. At the time of the 1965 X-Ray examination, Professor S. Oosthuizen, Chairman of the Medical Council, was of the opinion that the mummy was female. However, the face painted on the linen is that of a man, The typical Fayum-style encaustic portrait, in surprisingly good condition, dates the mummy to the second or third century CE. The Museum is engaged in a research project on the mummy, in association with the Anatomy Department of the University of Pretoria.

The ‘Pretoria mummy’ portrait is published in two publications of the J. Paul Getty Museum – The artists of the mummy portraits (1976), and Mummy Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum (1982), both edited by David L. Thompson. The portrait was also published in South African Panorama, July 1989, in an article (p.18) by Adrie Pillans, entitled “A voice from the past’.

NATIONAL CULTURAL HISTORY MUSEUM

De Villiershof 139 Mears Street,

Sunnyside, Pretoria, 0132,

South Africa

Telephone: (012) 341 1320

Fax: (012) 341 6146

Website: http://home.global.co.za/~nchm

MUMMY POST-SCRIPT

Johannesburg (Mail and Guardian, July 23, 1999)

Deep in a cave in the Eastern Cape’s forbidding Kouga Mountains lies the body of “Moses”, estimated to be about 2 000 years old. His is the first mummified human remains found in South Africa.

The Egyptians and the Incas mummified the bodies of their god-kings for their journeys through the afterlife, and so, it appears, did the San, the nomadic hunter- gatherer clans who were Southern Africa’s first people. This mummy could be a boost for tourism in a region otherwise starved of resources. But if it has a curse, it is the slashed subsidy and uncertain future of the Albany Museum of Natural History in Grahamstown, whose renowned archaeologist, Dr Johan Binneman, first stumbled across “Moses”. Binneman found him under two layers of bushes, sticks and a rare painted gravestone in April. He had been excavating the shelter where the mummy was found and its surrounds – which he now believes hold further remains – for several years as part of an investigation into the way people lived over the past 10 000 years. “It’s a beautiful place and unique – nowhere else in the world can you walk into the shelters and get a complete record of the past,” he says.

Moses was found in the dust of one of several holes at the back of the shelter. Binneman was following a simple urge to “neaten up” the shelter and the find was a “fluke”. “I decided to begin cleaning out these hollows, bag whatever I found and level the floor of the shelter. I could have chosen any one of about 20 holes.”

What he had found, as important and astounding as the mummy he would only find the next day, was something that had long been in dispute. Amateur archaeologists had reported finding such painted “burial stones” at assumed San burial sites in the 1920s and 1930s. When he returned to the cave the next day to lift the stone, Binneman found a thick layer of plant material, bulbs and leaves woven into a giant basket that he gingerly began to remove – to reveal the body, lying on its left side in a foetal position, and wrapped in a medicinal leaf known as boophone that is still used as a bandage in Xhosa circumcision rites.

The boophone “clearly has some preservative and insecticide quality as well, which kept the bacteria and flesh-eating organisms away”, Binneman said. “The body has simply dried up.”

Besides the leaves keeping out decomposing bacteria and fungi, the body’s remarkable state of preservation was also enhanced by the dryness of the environment.

Once the boophone was removed, parchment-like skin and toenails showed through. A length of rope-like cord wrapped around the ankles and disappearing up to the upper torso, which Binneman has not yet exposed, was further indication of a San burial. Binneman identified the cord as made from the vleibessie plant that was apparently part of the preparation for burial. Traditionally, a Khoisan body was forced into a foetal position for burial, with the cord to keep the body in position. Ostrich eggshell beads and bits of pottery were also found around the head. Bulbs found with the remains were so well preserved that the archaeologist could pinpoint burial to August or September.

Binneman had discovered South Africa’s first mummy. But his troubles were just beginning. He still needed to date and sex the body, and carry out other tests requiring specialised input and a lot of money.

Dating costs R1 500 (US$ 250), and it is money that the Albany Museum does not have. The museum’s provincial government subsidy was slashed to crisis proportions last year as it squared up to retrenchments and possible sale to Rhodes University that Bisho inexplicably refused to clear.

Compounding matters, the fragile mummy would also have to be moved – requiring proper exhumation, preservation against further deterioration and careful transportation down the wild mountainside and then to Grahamstown. And Binneman would have to do all this fast, for the mummy had already been partially exposed to the elements and required rapid preservation to stop it crumbling to dust. And then arrived the deputy director of arts and culture in the Humansdorp area, John Witbooi, representing a local group calling itself the Khoisan Awareness Initiative. It was claiming heritage ties and was dead set against transporting the mummy to the museum.

To remove the remains would be to reduce them to a “scientific freak”, Witbooi said. The use of plant preservation had shown the Khoi and San to be far from being the “primitives” history made them out to be, he said, adding the remains were likely to become entangled in a “tug of war for tourism” instead of the discovery being handled in a dignified and sensitive manner. It took two nerve-wracking months of negotiation to satisfy the stakeholders that the remains would be handled “in a dignified manner” before Eastern Cape museums director Denver Webb could announce that the mummy would be exhumed and transported to Grahamstown.

The museum will be trying to raise funds for the exercise, and a deal has been worked out with the University of the Witwatersrand for scientific studies to be undertaken and completed within the next two years. Further consultations and the examination of overseas models will determine the mummy’s final resting place, said Webb, whose department was “not in favour of gratuitous display” of such discoveries. Options include reburial or the building of a “house of memory” near Joubertina. The museum, meanwhile, is handling the costs for the removal of the mummy, which finally got under way this week. For a brief moment once more, Binneman and “Moses” are reunited in the Kouga Mountains – but this time one step away from an identity and a special place in our hitherto neglected history.